Analytical quality assessment tool, also known as External Control, has more effective use in the laboratory if some attributes are considered

To produce reliable and consistent data, analytical routines must implement an adequate quality assurance program and performance monitoring process. Proficiency Testing is one such routine. It is an effective quality control tool in determining the performance of the laboratory’s analytical phase. When used in conjunction with Internal Control and management committed to quality, it helps to promote knowledge of analysis processes and guarantees the laboratory the reliability of its results.

Proficiency Testing and Internal Control are complementary. Together, they have the central purpose of identifying the presence of possible analytical errors, enabling the laboratory to implement actions to eliminate the causes of these errors.

The Proficiency Testing monitors process trends (inaccuracy), commonly related to linearity, specificity, sensitivity, interferences and calibration characteristics.

Internal Control, in turn, is carried out together with the routine analysis of patient samples, with the aim of validating the results produced after identifying that the analytical system is operating within the pre-defined tolerance limits; the focus is given in particular to the accuracy of the process (reproducibility).

Proficiency Testing Frequency

As this is a control that monitors the analytical quality of the laboratory, the frequency of the program must be continuous and can be analyzed from three aspects: number of annual rounds, quantity of different materials supplied in one round and quantity of dosages performed on each material. The multiplication of these three pieces of information determines the number of annual measurements performed. In single programs (single round), the first aspect is eliminated and, thus, the quality of monitoring ends up being reduced.

An appropriate frequency must be determined by balancing a few factors:

• difficulty/ease of executing the program;

• representativeness in relation to the laboratory’s routine;

• consistency of results against the purpose of the test;

• cost benefit;

• ability to obtain the material;

• rate of change of the processes involved (change of analytical system, staff turnover, update of analytical requirements) and

• program effectiveness.

A risk-focused approach to the patient also considers whether the assay involved is high risk, whether it supports clinical decisions, whether it is performed on samples that are difficult or painful to collect, and/or whether it performs poorly.

The practice of very short intervals between rounds, such as four weeks, can be a problem because it encourages the use of the Proficiency Testing in place of the Internal Control, since a controlled routine does not have the incidence of systematic error with such a short frequency. It is also minimally expected that the adopted system be more stable and that the settings defined in the use of internal quality control have sensitivity to identify significant changes in daily processes.

On the other hand, intervals longer than four months can reduce the impact of the program, as it takes too long to help the laboratory identify and correct analytical failures, which is generally related to calibration errors or improper maintenance that may occur during this period.

Reductions in frequency (number of annual rounds and quantity of materials per round) are commonly observed when there is a restriction on obtaining or preparing materials, or even when the costs associated with preparing the material, maintaining the Proficiency Testing or carrying out the analyzes by the laboratory are excessively high, to the point of making the program unfeasible. In these cases, alternative controls should be used to maximize monitoring of the analytical process.

In summary, for a good assessment of the frequency aspect of the Proficiency Testing, it is necessary to consider the following routine questions: How often does the laboratory identify a systemic error in the process? With what constancy does the analytical process undergo changes regarding new calibration, maintenance, new operators and other interferences?

Number of different materials in the Proficiency Testing

In view of the main purpose of the Proficiency Testing, specialists have defended the importance of abandoning the practice of using a single material per comparison round, as it does not contribute to the differentiation of random and systematic error, that is, the identification of trends. In this context, suppliers all over the world have adopted at least two different materials per round (in situations with restrictions), which can reach five materials in routine tests for which the restrictions mentioned above do not apply.

A single piece of data does not indicate the repetition of an error and does not allow estimating or concluding that it is a systematic error. While a single result only allows estimating the total error – the difference between the laboratory result and the target value –, from two results it is possible to estimate the systematic error – mean of the relative total errors.

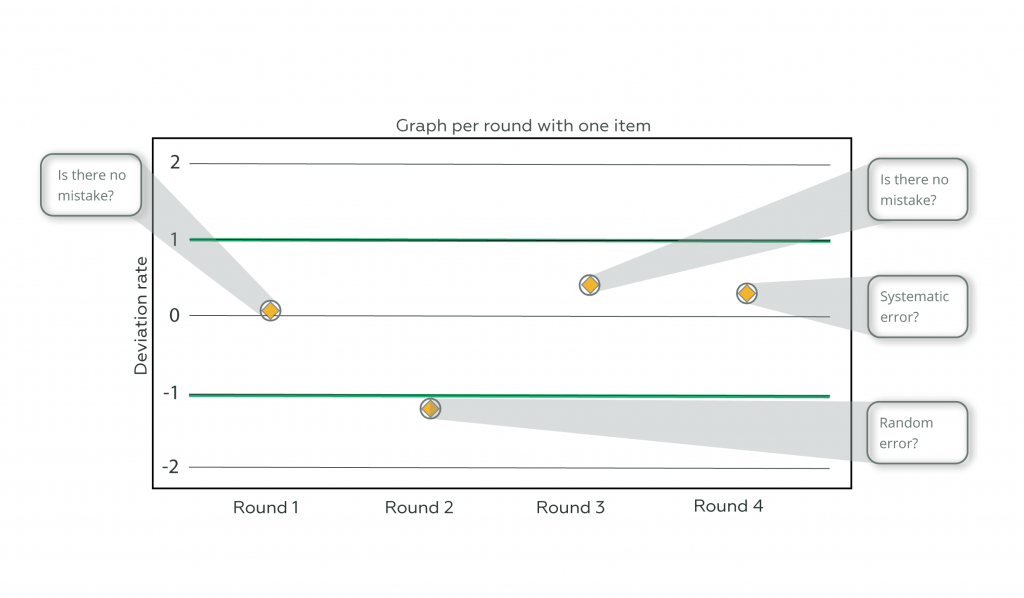

What is described in the previous paragraph can be exemplified in the graphs below, which were constructed from a real case. See chart 1, where only one item is sent in the Proficiency Testing. Try to estimate the type of error (systematic or random) present in the routine and you will notice that we only have guesses.

Graph 1

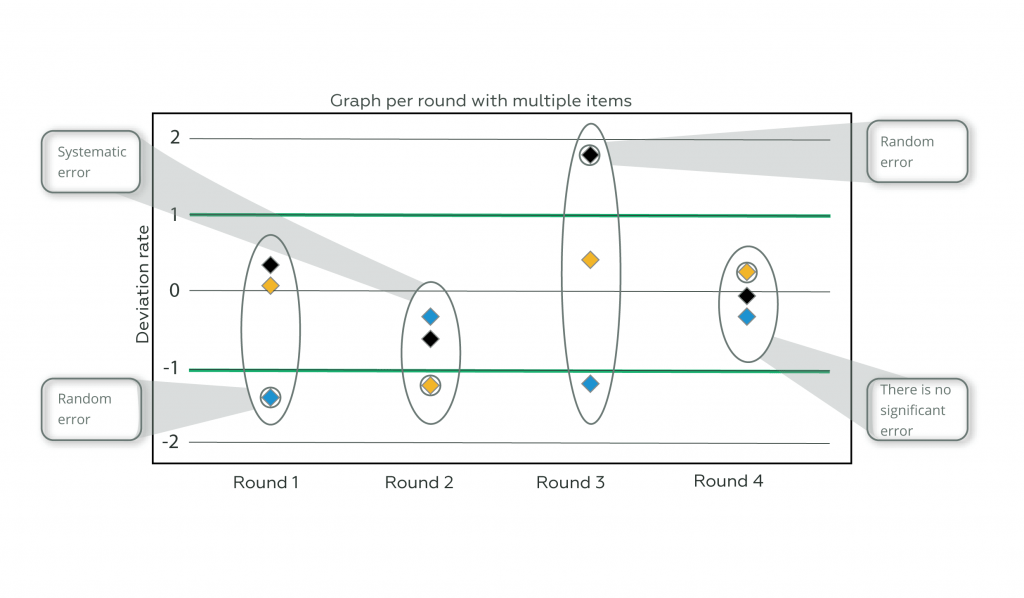

Now, observe this same performance shown in Graph 2, where multiple items are sent in the Proficiency Testing and realize how much more assertive we can be in identifying the type of error present in the process and in defining corrective actions.

Graph 2

Note that, in round 1, looking at the graph where only one test item is submitted, it may initially appear that there is no evidence of any kind of error. Comparing this same round on the multi-item plot, we identified a random error.

In round 2, where graph 1 can lead to a possible interpretation of random error, a systematic error can be observed and the application of multiple items optimizes the efforts of critical analysis and performance investigation.

Round 3, with multiple items, shows a large variation that cannot be identified in the single item chart; while round 4, in the multi-item chart, does not show a significant deviation from the provider’s criterion. It is concluded, therefore, that the application of multiple items enriches the critical analysis of the analytical behavior of the routines.

On the other hand, larger amounts of material per run are justified when one wants to obtain more reliable estimates of systematic error, cover a wide range of readings within a single run, or avoid predictability of results in qualitative assays. However, very high numbers of items can make the program more expensive. Measurements with more items can be performed at more spaced intervals, such as in revalidations, when there is a need to redo it in view of what has been observed in the Proficiency Testing and in the Internal Control.

Periodicity of the Proficiency Testing

In practice, programs intended for clinical and blood therapy laboratories are usually continuous, with a single dose (one dose per material), from four months to monthly, annually adding 8 to 15 different materials for each test. Providers adopt a frequency pattern for most tests, but adapt this pattern (usually reducing or increasing the amount of materials per round) according to the reality of some tests.

Another relevant point to be considered to assess the need for high frequency is the continuous participation of the Proficiency Testing in parallel with other control actions and analytical management tools, such as Internal Control, Calibration, Linearity Studies, etc. Such actions associated with robust, well-controlled and stable analytical systems (without constant changes) allow greater process stability and greater spacing of the proficiency test, without prejudice to the monitoring of the results produced in the routine.

It is worth mentioning that, if the laboratory frequently presents systematic errors, it must evaluate its process and/or analytical system adopted in the routine, aiming at adjustments to minimize these impacts.

Impartiality of the Proficiency Testing Provider

Another aspect to be evaluated is the impartiality of the Proficiency Testing provider in relation to the set of information that is evaluated in the service, such as: supply of reagents, systems or other related inputs. It is up to the provider to impartially demonstrate the behavior of the market in relation to the analytical sets used by the laboratories.

A valuable source of information on these and other aspects of Proficiency Testing is available in the book Management of the Laboratory Analytical Phase – How to Assure Quality in Practice (vol. II).